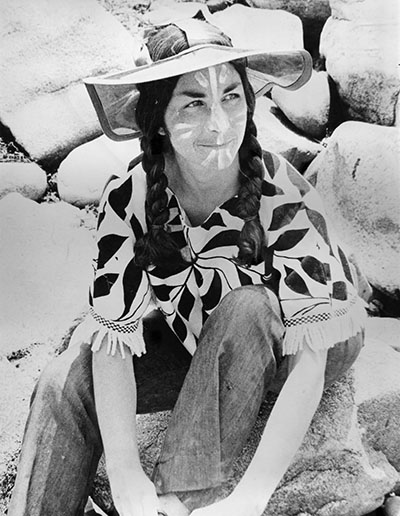

Roz Payne Bio

Roz Payne was born in Patterson, New Jersey, and grew up in a political household. Her mom, Edith Berkman, was of Jewish and Polish descent and a Communist labor organizer. She was arrested during the Lawrence, Massachusetts, textile strike in 1931. Afterward, the U.S. Department of Labor attempted to deport Berkman to Poland. Berkman was held in Boston by the U.S. government without bail for more than seven months. During that time, she developed tuberculosis and engaged in a hunger strike. Her case became fairly well-known among radical activists and labor organizers at the time, particularly on the East Coast. Payne’s father, James Cristiano, was Italian Catholic and ran for the New Jersey state legislature on the Socialist Party line. She recalled as a child listening with interest to the regular political discussions between her parents and their friends at dinner parties and other gatherings. Beat poet, Allen Ginsburg, whose parents were friends with Payne’s folks, was also her occasional babysitter. As she later told Vermont Woman Magazine reporter, Margaret Michniewicz, "I came from a very political home, and had a Leftist background, let's say. My parents were really activists against racial discrimination; they talked a lot about equality as part of our day-to-day life. It was the fifties and schools were being desegregated, and friends of mine were doing Freedom Rides, going to Mississippi to work in the summer. I didn't do that but it was part of my background." In a 2014 interview, she remarked, "I grew up being a radical person. I didn’t have any choice."

Ultimately, Payne’s family moved to Los Angeles, where she attended high school and graduated from UCLA. It was in California that Payne met and married her high school sweetheart, Arnold Payne, or “Mr. Muscle Beach,” as she referred to him. The couple moved back to New Jersey, where Payne earned a master’s degree at the City College of New York and began to teach. By 1967, though, her marriage to Arnold had dissolved and Payne began to sour on the strictures associated with being a school teacher in the increasingly fraught political context of the Sixties. Her values and interests moved her increasingly toward activism.

Payne, who was also a photographer, joined Newsreel Films in 1967, “a group of independent filmmakers, photographers, and media workers [that had] formed a collective to make politically relevant films sharing our resources, skills, and equipment.” In a reflection published on her website, Payne recalled the early history of Newsreel:

“Walking down Second Ave and 10th Street with my camera one afternoon Melvin Margolis, a wild looking hippie, stopped me and said, ‘Hey, you're a photographer and there's a meeting tonight of all the political film people. You have to go. It is very important. Make sure that you go. I'm not kidding.’ I showed up that night, to the first meeting of Newsreel."

In another interview, Payne shared, "I walked into this room and... I saw the most beautiful people I’d ever seen in my life. They all seemed like they were my people. I wanted to hang out with them; I wanted to be with them. And that was the first meeting of New York Newsreel."

Continuing from her website, she said: "About 30 people met weekly to talk about films, equipment, and politics. I think we were great because we came from various political backgrounds and had different interests.

We never all agreed on a political line. We broke down into smaller groups to work on the films. The working groups included anti-Vietnam-war, anti-imperialist, high school, students, women, workers, Yippies, Third World, and the infamous sex, drugs and party committee. We wanted to make two films a month and get 12 prints of each film out to groups across the country. We wanted to spark the creation of similar news-film groups in other major cities of the United States so that they would distribute our films and would cover and shoot the events in their area.”

Ultimately, Newsreel had offices in San Francisco, Detroit, Boston, St. Louis, Los Angeles, Vermont, and Atlanta. “We made films and distributed our films in the hope that the audiences who saw them would respond to the issues they raised," Payne stated. “We wanted people to work with our films as catalysts for political discussions about social change in America and to relate the questions in the films to issues in their own communities.”

In a very real sense, the films Newsreel created were organizing tools. "The only news we saw was on TV and we knew who owned the stations,” she wrote on her website. “We decided to make films that would show another side to the news. It was clear to us that the established forms of media were not going to approach those subjects which threaten their very existence. Our films tried to analyze, not just cover, the realities that the media, as part of the system, always ignores. We didn't like to just send our films out; we would go out and speak with our films. We saw them as weapons. We hoped to serve as part of the catalyst for revolutionary social change."

Payne’s first assignment with the media collective was to document the 1968 occupation of Columbia University by members of the Students for a Democratic Society and Student Afro-Society. As Payne recalled, “The students had taken over 5 buildings. We had a film team in each building. We were shooting from the inside while the rest of the press were outside. We participated in the political negotiations and discussions. Our cameras were used as weapons as well as recording the events.”

Payne had a particularly close relationship with the Black Panther Party and played a key role documenting, in photographs and film, a number of key events in their history, including the Free Huey! campaign in 1969, the trial of Bobby Seale and nine other Panthers in New Haven, Connecticut, the same year, and the demonstrations surrounding the Panther 21 arrests and trials in New York during the early-1970s. Newsreel is perhaps most famous for the three short films they produced on the Panthers - “Off the Pig,” “Mayday” and “Repression.” Payne related how Panther leader, Zayd Shakur, asked her to show Newsreel films to new Black Panther Party recruits and younger party members as a part of their political education. On Monday nights at their Harlem branch headquarters, Payne would “take one of our projectors in a case - projectors are pretty heavy, by the way - and maybe two films under my arms and my purse and I'd take the subway up to Harlem, get out and walk a number of blocks to the Panther office. I'd set up the projector and show films and lead discussion. I'd show films on the Panthers, or the war in Vietnam, maybe some other issue happening in the US, and we'd have a discussion. And then, I'd pack up my stuff and go back [downtown]. We let the Panthers use our dark room, taught them photography techniques. We considered them comrades. They always treated me with great respect and we had a lovely relationship. We were in partnership in our struggle.”

And Newsreel had a global perspective. Again, Payne explained, “Newsreel not only made films but we were among the first to distribute films made in Cuba, Vietnam, Africa, and the Middle East.” For instance, “Por Primeria Vez,” or “For the First Time,” was created by the Cuban Film Institute, documented a project where mobile film units were sent into rural provinces in Cuba to screen “Modern Times” by Charlie Chaplin, the first time most of the people in those villages had ever seen a film. “People’s War” sought to “move beyond the perception of the North Vietnamese as victims to a portrait of how the North Vietnamese society is organized.” “Seventy-Nine Springs of Ho Chi Minh” drew on still photographs and footage captured inside the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to present the life and death of Ho Chi Minh. “Young Puppeteers of South Vietnam” tells the story of teenagers in areas controlled by the National Liberation Front, who create puppets from the scraps of U.S. military materials and perform for local children. Or, “Venceremos” portrays the 1970-71 contingent of U.S. leftists who travelled to Cuba on a solidarity mission against the wishes of the U.S. government. “El Pueblo Se Levanta,” or “The People are Rising,” documents the activism of the Young Lords in New York City and the struggle for Puerto Rican independence. And, “Ice,” a feature-length film by Newsreel member, Robert Kramer, offers a futuristic look at a war between the United States and Mexico.

In addition to her work with Newsreel, Roz Payne was active or present at an astonishing number of other important moments during the 1960s. For example, she was close with Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies, documented the famous 1967 anti-war demonstration at the Pentagon, as well as the Rankin Brigade march in Washington, D.C. in early 1968 and the infamous turbulence outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago later that year. Payne often tells the stories of being one of the folks at Woodstock in 1969 who would go out each day and loosen up fencing to allow people to enter without tickets, or how she ended up with the original blueprints to the festival. She was a founding member of the radical feminist group, W.I.T.C.H. (“Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell”) and travelled to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade. Payne had connections to the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords, SDS and many other New Left organizations. She was also involved in dozens of smaller, lesser-known actions during this period.

In the early, 1970s, Payne moved to Vermont, where she joined her friends, John Douglas, Jane Kramer, Robert Kramer and others at the "Green Mountain Red" commune in Putney, Vermont. "There were piles of communes in those days," she remembered, "and once a year we would have commune reunions. For example, at the Franklin [Vermont] Commune, we all gathered when they were going to pick animal feed corn. It was hilarious. They gave us bags to put on to pick the corn. All the community in Franklin was along the road looking at us. We went up and down the rows picking corn and throwing them into the bags. Those people are still my friends."

Over the years, Roz Payne continued her activism on a number of local issues, including helping to launch the political career of Bernie Sanders. She even ran for sheriff and won. In addition, Payne maintained her archive of Sixties materials and often shared her knowledge and perspective with community groups, students and scholars across the country. Roz Payne passed away on May 22, 2019.

The Roz Payne Sixties Archive stands as a living testament to Payne’s life, one lived passionately and radically in service to justice.